A Swiss colleague recently mentioned to me that many of his customers in the machinery and industrial equipment industry are burdened by the longevity of their products. Some were designed and manufactured so well that many customers saw no need for replacement – even after decades of service. An interesting aspect!

First of all, it triggers the question: is it good or bad that products are so reliable that they last for decades? For a manufacturer it is both. The positive aspect is that it contributes to a reputation of reliability and quality which will, of course, help win new customers. But on the other hand it will limit selling opportunities to the existing customer base, which could mean that the valued manufacturer’s profitability and financial stability becomes compromised over time.

Planned obsolescence – one century old… and not obsolete

It is an obvious reflex at this point to think about planned obsolescence: designing products in a way that they become useless after a calculated period of time. Which, of course, raises moral concerns – especially for those who have an unrelenting commitment to quality like our friends in Switzerland.

But we also need to consider that usefulness of a product is not only determined by its longevity. It can also be limited by technological progress, i.e. by the appearance of new products that are better suited to meet the requirements of an evolving marketplace.

In fact, the term planned obsolescence is almost 100 years old. It appears to have been coined in the 1920s when the automotive market in the United States began reaching saturation for the first time. To maintain unit sales, the head of General Motors, Alfred P. Sloan Jr., suggested annual model-year design changes to convince car owners that they needed to buy a new replacement at regular intervals. Critics called his strategy “planned obsolescence”. Other sources attribute the term to a pamphlet “Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence” published by the real estate broker Bernard London in 1934.

It all depends on the use profile and service life

So, while quality and reliability is beyond doubt a good and valuable virtue for every manufacturer, it equally makes sense to identify and plan the prospective usage profile and service life of a product for the mutual benefit of both the customer and the supplier. While in the investment goods market the focus will be on operating cost, reliability and depreciation; in other areas, such as computing and mobile communication, innovation, performance and affordability are the key factors.

Consider mobile phones – a market where the majority of buyers purchases a replacement every other year on average. It wouldn’t make sense to build a mobile phone to last 20 years at a much higher price. However, other factors may come into the equation such as design for recyclability –designing both the product and supply chain to enable a reasonable reuse of precious resources.

Cultivating a tightly managed product lifecycle

Whatever your strategy, it is essential that a product is designed to satisfy the customer’s expectation. That may be reliability and return on investment in the investment goods market; or a gratifying user experience for predefined period of use in the consumer market. In both cases, if the promise is broken, the customer will inevitably be frustrated and alienated. In other words, it’s all about keeping your promise, whether that is for 20 months or 20 years.

To achieve this you need a carefully managed product lifecycle considering:

- Controlled materials and parts usage to ensure consistent quality;

- and realistic simulation of a product’s behaviour under normal operating conditions.

And this leads you down the path of finding product design tools that are capable of:

- Considering advanced manufacturing rules.

- Providing up-to-date information for reliable service and replacement parts supply.

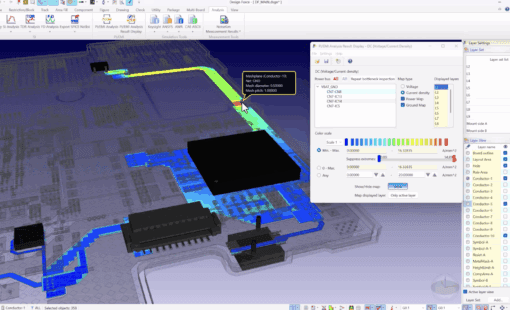

That’s what our customers pursue across the globe with their use of CR-8000 for the design of advanced high-speed, multi-board assemblies, and E3.series for designing leading edge electrical equipment. And that’s what we at Zuken have in mind when we develop and enhance our tools.

Related Products and Resources

- Products

- Products

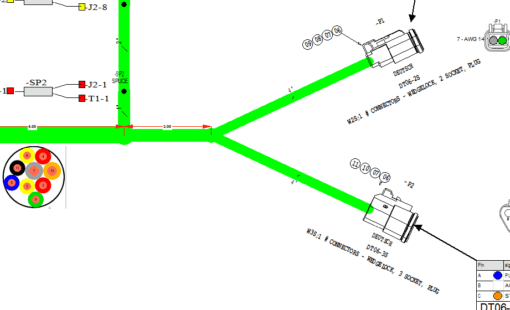

E3.series is a Windows-based, scalable, easy-to-learn system for the design of wiring and control systems, hydraulics and pneumatics. The out-of-the-box solution includes schematic (for circuit and fluid diagrams), cable (for advanced electrical and fluid design), panel (for cabinet and panel layout), and formboard (for 1:1 wiring harness manufacturing drawings). Integrated with MCAD, E3.series is a complete design engineering solution from concept through physical realization and manufacturing output.

- Products

Zuken’s engineering data management platform DS-CR has been created to support the specific demands of PCB design data management. It combines multi-site library, design data and configuration management into a unified engineering environment.

- Products

Building a competitive product today is much more difficult than a few years ago. Existing PCB-centric design processes are limited to a single PCB and do not provide the necessary tools for today’s competitive product development environment. PCB-centric design processes are falling behind.